During an emotional and insightful first day of the 9th edition of The Power of Storytelling, the speakers talked about the burden and responsibility of telling complicated family stories, about transgenerational racism and social exclusion, and about how music, multi-platform journalism, active listening and remembering untold stories can contribute to personal and collective healing.

Here are some of the main ideas:

TATIANA ȚÎBULEAC

We kicked off the conference with one of the most unique voices writing in Romanian today, Tatiana Țîbuleac. Of Romanian descent, born and raised in Moldova and currently living in Paris, Tatiana took us on a journey of her family history and the difficulty she had in doing it justice.

“I always believed in healing from the inside and my story is a wound that took three generations to heal. There are three storytellers in my family: my grandmother, my mother and I. We’re a family that placed value on words above anything else.”

She took us through her grandparents’ tragedy of being deported to Siberia, that ended seven years later with two miracles: the death of Stalin and the birth of her mother, Vera. All the while, her grandparents were the glue that held a small community together in exile, with the help of an unlikely object: a needle.

“That needle came to life because, at some point, everyone seemed to need a needle to repair clothing. You couldn’t really buy it there; it was the kind of object you just possess. And no one thought to take a needle to Siberia. The needle brought them together,” Tatiana told the audience. The needle was passed to her mother later, who grew up in a very different country, Moldova, but nonetheless a country that had betrayed her family. When the time comes, Tatiana said, the needle with end up with her.

Through her writing, Tatiana hopes to make peace with her family’s history and to relieve the guilt of not having written about her country’s complicated past earlier, during her 15 years as a journalist.

“A family wound is not easy to heal and it requires more than one generation. Because healing means pain and suffering, but also forgiveness and making peace with yourself. Having a strong personal or national story can be a burden. But it can also be a very strong and inspirational source.

I encourage you to talk to your parents and grandparents while you still have them. These are your stories. If you don’t know them, you will feel incomplete.”

LUCIA

Lucia, a Romanian singer of modern indie pop, talked about how music helps her overcome her anxiety and about the need about having a deeper conversation on mental health.

“I felt the pressure when I started putting music online. People said it was nice, but it’s not my first song, that I was talented, but that I got lucky. I am lucky to be part of a generation that acquires skills from the internet. I learnt to play piano through Youtube. I am not good enough, my 17 years old brains told me. I was not a classically trained piano player or singer, I didn’t know how to play, but it was the only thing I knew how to do.”

She put pressure on herself and it did damage, but music taught her it can bring people together.

“I embraced Samsara at a certain point, an Indian religion which talks about everything going in circles, life-death. I relate to the concept. When you have an emotional luggage, this burden sits on your back, it’s sadness throughout the whole process. I feel I have a dark passenger I carry on my back. But what artists have in common, I feel, is picking up wounds, opening up every single time though music – it is a masoquistic thing, but necessary, the only way to heal completely, the chance to get over things. I feel that music is the perfect medium to have that conversation with yourself. Nobody talks about death at a dinner table, but putting into songs feels more natural.”

One of the songs came to her in order to heal the wounds caused by her anxiety, that became crippling since she started suffering from Depersonalisation Disorder. She lives her life as if it is a dream, but music keeps her grounded. And therapy.

“There’s a conversation about mental health we don’t have. As I grew up in a society where we’re not supposed to talk about it, I used to look at people that had to go through life biting their lips, not saying anything. I think people need to know, and music is the easiest way for me to get my message through. I feel that I am not doing a great job talking, but things fit when I start singing. (…) The way I live my life is not necessarily wrong, feeling everything 110% is wrong, people told me, but I rather feel everything, than nothing at all.”

LIPI ROY

Lipi Roy, a board certified physician in addiction medicine, worked with prisoners and homeless people, trying to help them through their difficulties. She explained how she had not always been the most empathetic doctor to her patients, but she managed to change her perspective once she started researching addiction and discovered the leading cause of death in homeless people in Canada, where she lives, was drug use.

“I learned over time about the gaps in my own knowledge,” Lipi said. “Before I understood how addiction worked, I blamed patients. But by listening to their stories and learning brain biology, I gained a far better understanding of how it worked.”

She believes there’s a simple way to reduce stigma.

“Change the vocabulary. Words matter. When we use stigmatizing punitive language such as drug abuser, junkie, coke head, the effect on patients is that they are more likely to perceive discrimination and less likely to seek help. When we use compassionate, less judgemental language – like substance use disorder – people feel less judged, more respected, and are more likely to seek care.”

She also shared what she does to stay positive, present and focused on her work: meditate, practice yoga, keep a gratitude journal, spend time with friends, make sure she has time to do nothing. The most important thing, which she encouraged the audience to practice, is to ask for help when they need it.

LUKE DITTRICH

Luke Dittrich talked about his first book, the award-winning New York Times bestseller, Patient H.M.: A Story of Memory, Madness, and Family Secrets, which tells the story of one of the biggest medical experiments and about the hardship of reporting when you have to dig deep into your family history. Because what you find out might hurt.

“Henry was not a patient, he was a perfect experiment. In 1953, my grandfather stood in the operating room, sliced his cranium and drilled two wholes in his brain. The partial destruction of Henry’s brain leaved him without memories. He lived his next six decades in sequences of a 32 seconds memory. You could meet Henry, talk about the weather with him, and in two minutes introduce yourself again. Henry would never have any children, but he become the father of modern memory science. How are we supposed to write about the double edged subject like that?

My grandfather died when I was 10 years old and I have a few memories of him. I have a hippocampus, so I have what he took from Henry, a lot of stories. I heard about him before the book from my mother. He was fun, loving, kind of amazing adventurer of a guy, who had some flaws, but not that deep. Whenever she brought up Patient H.M., it was brought as one mistake he made. I remember the day I had a contract to write a book about him. I called my mom because I was excited to tell her. Her words were: oh, no. Even she didn’t know half of what I found out, things she didn’t know either, and my book caused her a lot of pain.

Another thing my mother learnt was that all my grandfather’s lobotomies had personal roots, as my grandmother was herself mentally ill, she was diagnosed with schizophrenia, and after she tried killing herself, my grandfather institutionalised her in one of the asylums he would perform lobotomies in. In this asylum my grandfather experienced with treatments such as electroshock therapy or heat induction. He wanted something painful and effective for his wife. In every brain he touched, at some desperate level, it was a step to curing his own wife.

Towards the end of my reporting, one of the most memorable experiences was sitting down with an old, venerated neuroscientist who knew my grandfather. When I asked him what he thought about him, he said. „Bill was a good man, but I could never trust a man who would lobotomise his own wife”. When I began digging, it was evidence to support that, during one of my grandmother’s institutionalisations, he designed a lobotomy for her, less impactful in some ways. That was a shock, wasn’t easy to learn, write about or tell my mother.

Patient H.M. had a black and white story (before the book). A brilliant group of researchers all teaming up to probe one of the fundamental mysteries of human history. I revealed the fact that the story was darker, not something you want to brag about it.

I would argue that journalism has something in common with surgeries. Like a heart surgeon, we can move a person’s heart. As a neourosurgeon, we might change a person’s mind.

With my book, I tried to reset Henry’s story, put it back together, aligning it more with the truth. It was a brutal job, with words, those crude instruments, but that pain grew apart, with distance. In my family, there is now a new appreciation for my grandmother, for all she endured. Stories do heal, but sometimes they will hurt like hell at first.”

ROBIN KWONG

The Financial Times’ Robin Kwong talked about how journalism should move beyond just offering facts as a service, and also think about providing empathy as a service. This comes as trust in the media is declining year after year, most notably in the UK where he works. As a result, he developed game design techniques and explored emotional storytelling based on factual reporting.

“We need a new form of journalism, journalism that remains very grounded in factual truth, but also that honors and speaks to emotional truths. We need to spark curiosity and encourage exploration and discovery. We need journalism that doesn’t just provide facts as a service, but also that provides empathy as a service. That’s what I’ve been trying to do.”

He, along with his team, developed the Uber Game to help people empathize with drivers in the gig economy; he based a game on the US-China trade war to make people experience the Kafkaesque feeling of navigating bureaucracies and stand-offs; he turned the Irish border problem into a poem recited by an actor, on the Irish border; he developed a theatre performance about climate change; and he’s preparing much more.

Check out his team’s latest news game, that puts you into the shoes of a chief executive who has to balance profit and purpose: https://ig.ft.com/esg-purpose-profit-game/.

AARON LAMMER

Aaron, the co-founder of Longform, a platform curating the best non-fiction writing from around the web, talked about the lessons he learnt after a couple of interview-podcasts he did along the years, food for thought for those in search of some courage to start something new. Here are some of his tips and insights:

- Force people to subscribe to your podcast: take their phone and go to the app and you picked up a listener. It is on you to teach people how it works.

- Be bad at podcasting. I thought you can put a mic in the middle of two people. The first 25 episodes of Longform Podcast are unlistenable. That said, I think persistence is key to do it. I didn’t feel comfortable up until episode 50. That means once a week, for a year, of being bad.

- Design it for your audience. It can be brutal to practice in public, but you should design for them. I got hung in the idea of what was the show about, but technical decisions like intros, for example, become easier when you imagine your audience.

- Be consistent, don’t find excuses. It’s not hard to clone a podcast, you can make all my podcasts with 100 euro and a spare bedroom. Hard is not missing a week in over 300 weeks. There is a lot of starting, but not a long run. When I started both shows, I decided to publish every week for a year. Failed on one of the accounts. But it changes the disposition, putting everything out every week, even if it’s bad. When you do something hundreds of times, some will be bad, but it still is a great motivator.

- Be intimate. I realised podcasting is different when I was in line at a coffee shop and someone recognised my voice and asked about a back pain I talked about in one of the episodes, eight months earlier. People are not interested in my life, but the feeling I got was of a personal relationship. Made sense in a way. I posted 80-90 hours with me talking in a year. Might be more than the time you spend with friends, with your spouse, if you listen to it all. That opens new possibilities, it led me to think it is not about me. My reason to be open is to encourage others to be open.

MAX LINSKY

Max Linsky, co-founder of Pineapple Street Media, nd co-host of With Her with Hillary Clinton, followed Aaron on stage and shared some key lessons he learned about interviewing after seven years of making the Longform podcast:

- Give a shit – it matters the most. Podcasting is a very unforgiving medium to bullshit. You can’t fake it. If you don’t care, people can hear it.

- Be prepared, but don’t come up with a crazy list of questions that you read verbatim in front of someone. I did that at first. You’re staring at your questions when someone is talking. It’s a bad scene, you miss interesting story threads. I want to know where I’m going, but I have no road map.

- Set your ground rules. I say the same thing to people every time before an interview: “If I ask you something that’s too personal, just tell me and I’ll move on”. It makes things clear and it also says “I’m going to ask you some really personal questions”.

- Be game to sound dumb. It’s hard, but the interview is about the guest and not about you. Your job is to get the best out of them. So ask a simple question that’s straightforward – no one cares how smart you are and how much context you can insert into a question.

- Listen, listen, listen. The best interviews are the ones where you’re present, you’re not looking at your notes, you’re caring. It’s easier said than done, of course you get anxious sitting alone in a room with someone. But that is key to achieving your goal, which is to get people to think out loud.

IOANIDA COSTACHE

Ioanida Costache, a musician, videographer, and Roma activist that works to unravel a song-story tightly wound to Romani music, talked about the roma-trauma and how empathy might be the only way to heal it.

“Ethnicity was something better to hide for me. My blood was rushing to my cheeks because I did not look like my Romanian friends. I learnt how to live like a reaction to a stereotype.

Something unique about Roma trauma is that it was muted and destorted for centuries. What are the conditions that made me stay blind until 25 to the suffering of my own people?

Despite I am Roma, I learnt late about the Genocide of the World War 2. There was a rupture between myself and my ethnicity, I was shocked and appauled, I was ignorant of an event that could exterminate my own family.

Collective memory is beginning to fade. Testimony is important. By conjuring empathy, specificity, humanity, reigniting memory, breaking the culture of silence, we can make sure history is not repeating itself.

Healing recquires recognition, so we can recon reconciliation. Everything I do will afect you, everything you do will affect me. We have to ask ourselves: what do you carry forward?

Roma carry pain, but they cannot be the only ones carrying memory alive.

Through music, indvidiual memory becomes collective, and that is essential to healing. In order for the wounds to heal, they should be attended, not ignored, brushed. The preservation of memory is important. It is impossible to heal from trauma without someone to care.

The stories we tell about Roma desperately need to change. The narrative has the power to constitute who we are.

Before healing comes hurt. An injury needs attention. It hurts me thinking of someone seeing my dad’s dark skin and judging him. We carry the burden of those we love, who are hurt. It is called empathy, and it is the only hope, the only way, as a society, to gradually heal.”

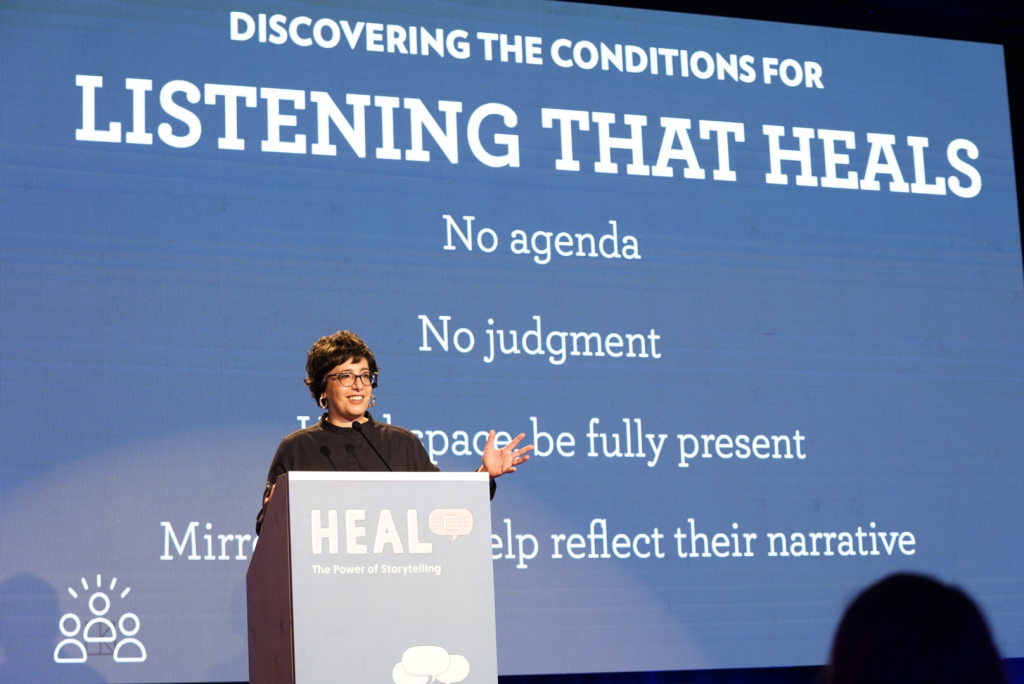

JENNIFER BRANDEL

From working for the Bahá’í faith and translating their religion into common language for other people to understand, to becoming a journalist and then a social entrepreneur advocating for public-power journalism, Jennifer Brandel follows a few lessons that might help everyone live and work better:

- You can focus on healing broken systems or on creating new systems that heal;

- Take a humble posture of learning that forces you to be a student (when you take a position of authority, you close yourself off to the world);

- You have to be curious in a relationship. The deeper you listen, the more specifically you understand. Do listening that heals – with no agenda, no judgment.

- Hold space for the other and be fully present. Mirror people, help reflect their narrative.

She also shared a few rules for action:

- If you don’t like what’s happening in a field, change the game by working outside the system. Don’t try to change the mind of an organization that you’re in.

- Change the story: get people to join your cause and grow it together.

- Change the equation – activate networks to exercise that new power.

Photos: Vlad Cupșa and Cătălin Georgescu